Seeing evocative images depicting negative scenes can activate various brain regions, and prompt an improvement in a person’s memory, a new study has found.

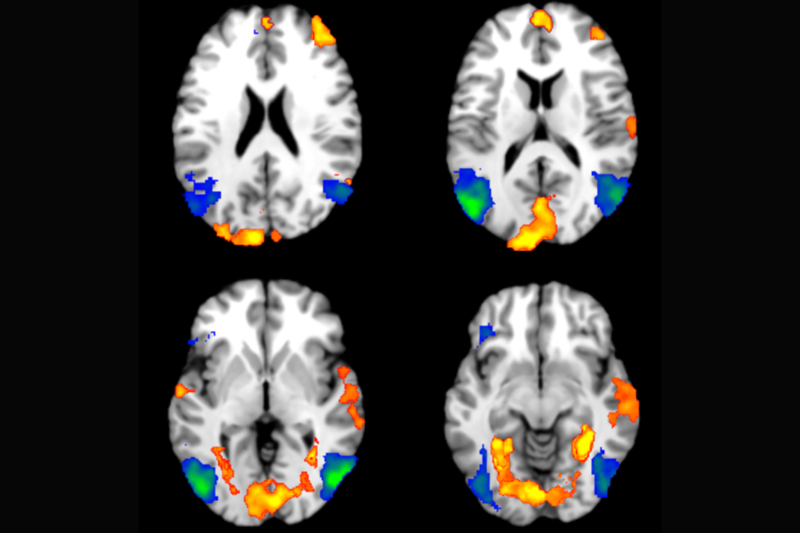

The trial by Bournemouth and Swansea Universities showed that participants were better at recalling information after seeing a negatively arousing image, compared to a neutral image. Functional MRI (fMRI) scans showed distinct brain activity patterns were associated with the negative images, closely linked to regions associated with memory performance.

The findings were true for tests of their semantic memory – the ability to recall facts – and for their episodic memory – how well they can recall specific experiences.

The results have been published in the journal Neuropsychologia.

“The study shows how interconnected the brain is and how manipulating the emotional networks can influence the systems involved in memory retrieval,” said Marianna Constantinou from the Department of Psychology at Bournemouth University, first author of the study.

Forty-seven participants took part in a series of memory tests whilst in an MRI scanner at Swansea University. A screen showed them a series of images that were either negatively arousing, for example a graphic scene of a major surgical procedure, or neutral, for example a photo of a park.

After seeing an image for four seconds, they were asked a question about the image itself to test their episodic memory, and a question on general knowledge, to evaluate their semantic memory.

The negatively arousing images were linked to more correct answers and a faster response time, whilst the fMRI data revealed the effects the images had on the participants’ brain activity.

When participants were recalling memories after seeing the negatively arousing images the fMRI scans showed more activity in the frontal lobes, which deal with decision making, and at the back of the brain, which is about vision. The researchers also noticed more activity deeper in the brain, in the Parahippocampus and Insula, which are both linked to memory retrieval.

“Our study shows that a negative image, very rich in context, has an effect, interestingly, translating into improved performance. This effect extends beyond participants retrieving details about the image itself; it also enhances performance when they are asked to retrieve something semantic, unrelated to the image,” Marianna said. “Since our study was conducted the brain scanner, we also found support from a neural perspective and we saw that there are areas in the brain which are activated more when people are better in recalling memories,” she added.

In future studies, the researchers will explore more about the link they have discovered between arousal and memory recall, including how an arousing image could affect people’s ability to retireve information presented to them after exposure to an arousing image.

“I think the study suggests how interconnected the brain is, indicating that to enhance memory, it is not solely about focusing on the memory system but also considering the emotional system. So there is a potential suggestion that improving long-term memory might involve targeting emotional regulation and how we perceive emotions,” Marianna concluded.