BU's emeritus Professor Nigel Jump writes the latest in his series of blogs on the Dorset economy.

Last time, I looked at the long-term issues about the limits to economic growth and the need to build a consensus about what we value. The government’s current dilemmas over ‘green’ targets and HS2 infrastructure have brought these matters to the forefront of socio-political discussion. This time, I consider the current state of the economy and some near-term forecasts.

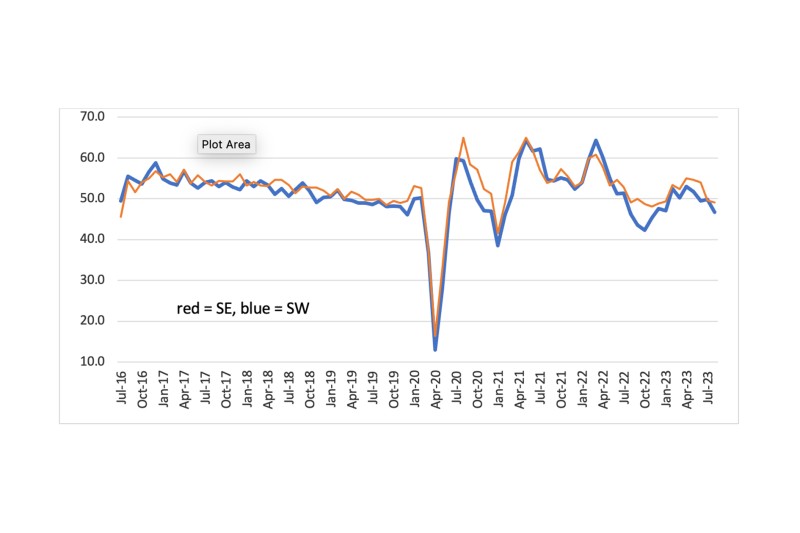

The first chart (below) shows how SW and SE England moved into a new phase of modest contraction around mid-year. The latest regional PMI surveys (purchasing managers) show new orders and backlogs shrinking in July and August. Employment was still high, but the overall position was down a little, with unemployment starting to rise and vacancies beginning to fall.

The PMI chart highlights the erratic nature of the economy’s path since the pandemic recession in 2020. We seem to be in a fourth period of falling activity (when the regional index is below 50). Overall, on this activity measure, two-thirds of the UK regions and nations (8 out of 12) were shrinking in August 2023. Anecdotal and other evidence, such as retail sales and housing prices, suggest there has been little or no change to this weak pattern in September.

PM ‘Activity’ Index

At a UK level, the latest statistics show a “flatline” in UK real GDP this year. The economy grew by only 0.1-0.2% in the first half of 2023. A recession was avoided, just. In July, however, there was a 0.5% fall and August was reportedly also weak.

- These “stagnation” figures will be revised but favourable weather and the coronation appeared to help some forms of consumer demand in early summer.

- Later, business confidence and demand for staff started to wane. In Q3, the NHS and other strikes tipped the numbers negative, whilst enthusiasm about prospects softened.

- Consumer resilience is now in question, (particularly in housing and related durables), reflecting higher interest rates and living costs (particularly related to foodstuffs, oil-linked energy, and many services).

- Meanwhile, supply chain problems persist. In July, production fell 0.7%, with a decline in manufacturing, electricity and gas, and water supply and sewerage; partially offset by a rise in mining and quarrying. Manufacturing output dropped in 9 of its 13 subsectors.

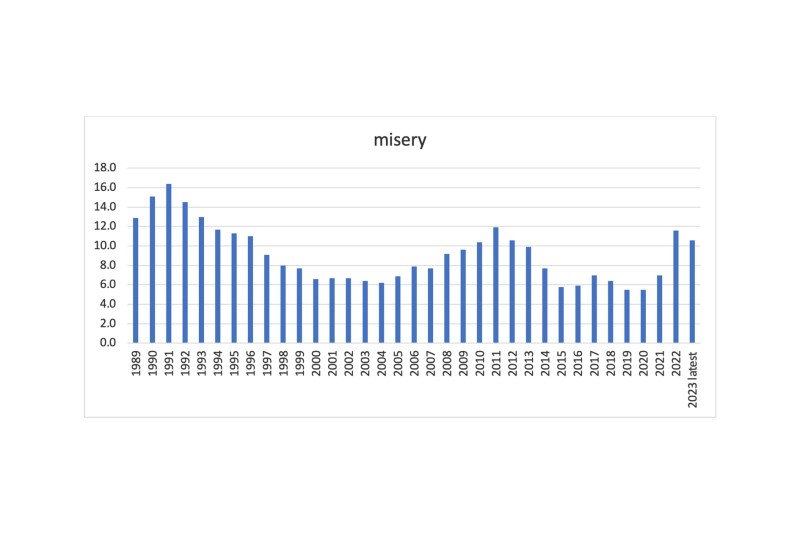

- Overall, the ‘misery’ index (CPIH inflation plus 16+ unemployment rate) may have peaked (see next chart below) but, it remains high.

The Bank of England predicts ‘stagflation’ continuing for some time (August Quarterly Bulletin). At its latest meeting (21 September), the MPC (Monetary Policy Committee) held its base interest rate steady at 5.25%, despite inflation not expected to get to target (2% CPI) before 2025. So, the upside inflation risks have not disappeared. At 5.25%, the official interest rate is still not tight in real or historical terms. Assuming it persists above 5%, this should create better incentives for productive investment, eventually. However, in the short run, with rates still below inflation, the period of tightening is probably not over. Better to act sooner rather than later to kill inflation and stop it becoming entrenched in a wide range of cost structures.

HM Treasury’s survey of independent forecasts for August shows predictions of growth, inflation, and unemployment rates of 0.3%, 4.5% and 4.2% respectively in 2023 and 0.6%, 2.6% and 4.4% in 2024. This consensus says the economy is broadly becalmed. It underlines the expected impact of the UK’s long accumulation of high debts and low investment across the public and private sectors. It sets a weak economic tone for the next General Election.

Today’s forecasts will be wrong, but in which direction? With the growth rate so close to zero, there is an obvious risk of dropping into recession (two consecutive negative quarters) in the second half of 2023 or over the upcoming winter. With prices and wages still rising strongly, though perhaps the pace is now slowing, there is also a risk of inflation remaining well above target. These risks of further “stagflation” or worse (with unemployment now ticking up), imply downward pressures on profits and jobs.

Is there anything on the upside to counter these concerns? Well, real incomes are starting to rise for some. Also, if uncertainty wanes, there may still be cash hoards out there available to boost expenditure. Moreover, the return to more ‘normal’ interest rates should mean better investment and consumption decisions in time. Still, a boost to business and household confidence is required to trigger renewed growth.

The following factors would help confidence:

- Peace in Ukraine and an easing of tensions in the Taiwan Strait and elsewhere.

- Resolution of some post-Brexit EU trade barriers and costs, and a waning of some of the “culture wars” ahead of America’s elections in 2024.

- At home, a more certain consensus on positive investment strategies from both public policy and private planners, especially regarding net-zero measures and infrastructure.

- A positive balance of UK opinion in favour of enhancing productivity (especially through innovation and the acquisition of new skills). ‘Collaboration in order to compete’ amongst businesses and households would go a long way to restore trust and confidence and to push development forward in sustainable and novel ways.

Until some of these materialise, the downside risks may outweigh the upside.

Whatever the short-term outlook, there is a need to get the basics right for the longer run. The World Bank’s data on GDP per head, adjusted for relative currency and inflation movements, shows the UK economy produced US$44,000 per head in 2017. This compared with US$47,000 in Germany and US$56,000 in the USA. By 2022, Germany and the US had grown this measure by 14%-15%, whereas the UK had grown less than 7%. At current rates of respective development, we will gradually slip down the league of macroeconomic performance (e.g., below Poland) on this key indicator.

Each country “chooses” how to “spend” its productivity in different ways, but it is the overall level and change of GDP per head that determines what can be afforded in terms of social and economic structures. Since 2008, the UK’s over-dependence on financial services, relatively slow recoveries, Covid19 damage, Brexit barriers, and policy errors have damaged our relative productivity and, therefore, comparative incomes.

The UK has ‘chosen’ a relative under-investment model in many areas (such as housing, health, education, transport, utilities, and production) since 2009. This has weakened our relative economic capacity. As a result, we tend to be hurt more by downturns and to be slower to turn around when they are over. Here’s hoping for a more concerned understanding and action about the links between long-term investment and short-term performance so that we are better prepared for the potential downside or upside risks.