Bournemouth University’s Emeritus Professor Nigel Jump writes the next in a series of blogs looking at the Dorset economy.

Right now, even if we discount the uncertain political environment, it is difficult to spin a positive tale about the economy. Yes, there is a danger of talking ourselves into a worse recession than we need, but we cannot ignore the reality of what’s happening and what is expected, especially with the Bank of England forecasting a two-year slump.

Nationally, with business and household confidence at historically low levels, we must endure cyclical and structural problems driven by multiple global and domestic trends. In particular, we face adverse effects on:

- the terms of trade, reflecting comparative price changes in a relatively weak sterling currency.

- investment and consumption, with substitutions stemming from differential cost-of-living trends (especially fuels, foods and debt/mortgage payments).

- real incomes, interest rates, and supply chains, especially given the labour and component scarcities that mirror lower worker participation and higher trade protectionism.

- retail sales volumes and public debt levels and ratios.

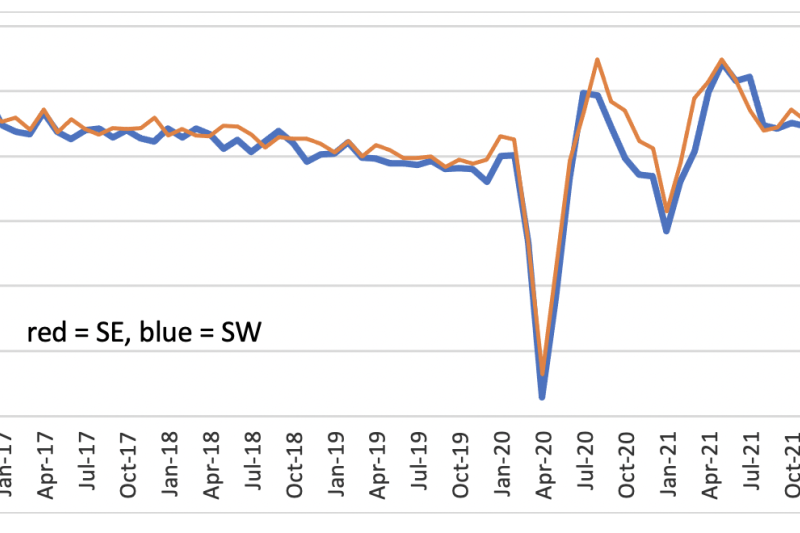

Regionally, it looks like SW England decoupled a little from the SE region in the third quarter and may have already started its recession (see PMI chart to August below). After three pandemic-related false recoveries, the Winter looks tricky for many industries and firms, as household and business-to-business exchange patterns adjust to cash flow restraints and non-discretionary spending pressures.

For any optimism, we have to look longer term. Although currently mired in crises of confidence in the bond and exchange rate markets, the government still hopes to raise the underlying long-term UK growth rate in real GDP (towards PM Truss’ 2.5% per annum target). A 2.5% per annum average is not that great in historical or comparative (with competitor countries) terms. But we have achieved less than 2% over the last decade or so. From where we are now, a permanent push to 2.5% p.a. requires significant positive structural change, raising sustainable productivity levels and rates of increase. The goal is worthy. The gap is wide.

Why is growth so important?

- with a rising population, some growth is needed merely to stand still.

- with a desire to increase living standards over time, (most people wish to get better off as they get older and to see their children better off over the generations), growth must tend to exceed the rate of demographic change. (Changes in population size, age distribution and its links to labour participation and aspirations are key to the targeted, desirable and achievable rate of growth.)

- with a need to move from a high carbon to a low carbon economy (see COP27), growth can act as a positive lubricant to fundamental physical and psychological economic change.

Next, we need to consider an answer to the question - growth of what? Growth of what we truly value is key and what we value changes over time. Also, there are important measurement issues. For example, I may want the value of natural asset flows to be weighted more highly in GDP but it is harder to measure these values than, say, the number of cars sold per annum. What is straightforwardly measured (in money terms) tends to be represented more in GDP than relative “intangibles”. GDP can be a backward looking variable if we are not careful. Going forward, it needs to be better measured in terms of carbon contribution as well as cash.

So, when politicians say they have a target to raise trend, average growth rates, they need to answer a series of questions:

- What are the demographic assumptions?

- What is valued, (in levels and proportions), and how will this change over time?

- What productivity enhancing investments or policy incentives will be made to effect the required change?

The answers we get need to be clear about:

- The effects of an ageing population (because it tends to lower growth potential through higher inactivity and dependence ratios) and migration (because it may counter an ageing population)

- The way we value and weight environmental and social services: relative to traditional manufacturing and consumer/business services, particularly when pursuing zero-carbon objectives

- The policies in place and how they intend to develop the drivers of productivity: infrastructure, innovation, skills, entrepreneurship and competitiveness

Meanwhile, as a forerunner to long term change, the Bank of England has to bear down on inflation. Its policy decisions on 3rd November recognised the need to soften aggregate demand further. It decided to:

- increase the base interest rate by 75 basis points to 3%,

- re-endorse quantitative tightening (begun this month), and

- alter forecasts of future inflation (target delayed), growth (prolonged slowdown) and unemployment (higher), and monetary conditions (tightening).

The Bank, however, is still ‘behind the curve’. Arguably, it has yet to tighten money supply and/or raise the price of money (interest rates) enough to dampen second-round inflationary effects (such as those arising from Putin’s war and those affecting domestic wage demands and profit margins).

The fiscal plans of PM Sunak/Chancellor Hunt, scheduled for release on 17th November, are expected to envisage a long-term supply side revolution whilst addressing an immediate fiscal ‘black hole’ of some £50bn. The trouble is measures (tax hikes and spending cuts) for the latter will squash demand immediately whilst meaningful supply reforms for the former will take years. We all face a short term hit to living standards before any structural improvements bear fruit.

It is possible to plan for a more optimistic future whilst fearing the here and now as we consider wealth creation and distribution through the current crises and beyond.