Divers have discovered the complete rudder of a 250-year-old warship on the bed of the Solent.

Diver surveys the newly uncovered rudder

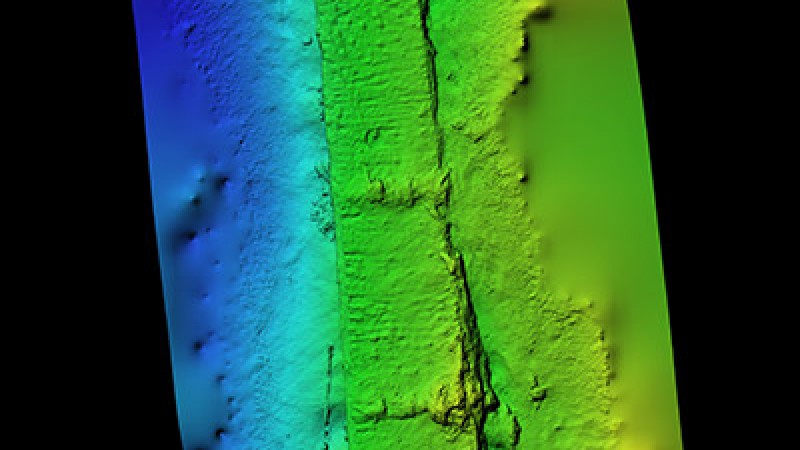

Diver surveys the newly uncovered rudderThe first HMS Invincible was captured from the French Navy in 1747 and sank off the coast of the Solent in 1758. Archaeologists and divers from Bournemouth University and the Marine Archaeology Sea Trust began excavating the wreck in 2017 but her rudder was never found. It is believed to have parted from the main stern and floated off as the ship ran aground.

However, on Tuesday 24th May, a team led by Bournemouth University finally found it, lying sixty metres from the original wreck site.

The rudder is complete from top to bottom and is over eleven metres long.

Dr Dan Pascoe, an archaeologist at Bournemouth University said: “We have conducted several routine surveys of the seabed, and had previously noted an anomaly in the sand, which I suspected could have been the rudder.

“Since then, natural erosion of the sand has revealed more of its secrets and our divers have finally been able to confirm where it has been hiding the missing piece of the puzzle.”

Dr Rachel Bynoe from the University of Southampton and Heather Anderson of the Maritime Archaeology Trust were the first from the Bournemouth marine dive team to see the rudder. A second dive by Tom Cousins of Bournemouth University and Lee Hall captured images and video footage of the discovery.

Originally L’Invincible, the 74-gun ship was built in France on the banks of the River Charente in 1744. Her service in the French Navy was short as she was captured at the first Battle of Finisterre on 3rd May 1747.

On 19th February 1757 Invincible began a voyage to Louisbourg (modern day Nova Scotia) but a series of calamitous events led to her wrecking on a shallow sand bank, seven metres down.

The wreck was discovered in 1979 by a local fisherman.

Whilst the rudder is in very good condition, there is risk that it could deteriorate now it is exposed to the elements in the sea, however recovering and conserving it on land would need financial investment.

Dr Pascoe explained: “In the short term we are going to bury it with sandbags to protect it from further erosion, then longer term our team are looking into whether it can be brought to the surface and preserved safely.”