Keith Parry, Bournemouth University

On Boxing Day 1920, a sell-out crowd of 53,000 watched a women’s football match at Liverpool’s Goodison Park, with others waiting outside. With more than 900,000 women working in munitions factories during the first world war, many factories set up women’s football teams to keep the new female workers healthy and safely occupied. At the time, women seemed to be breaking barriers in sport and society.

But it would be almost 100 years before similar numbers of spectators were seen again at women’s sports matches, and in 2022 crowds are now breaking world records. In March, for example, 91,553 people watched Barcelona play Real Madrid in the UEFA Women’s Champions League – the highest attended women’s football match of all time.

The reason why it took so long to get here is that after the first world war progress for women slowed, and even went backwards. By 1921 there were 150 women’s football teams, often playing to large crowds. But on 5 December 1921, the English Football Association’s consultative committee effectively banned women’s football citing a threat to women’s health as medical experts claimed football could damage women’s ability to have children. This decision had worldwide implications and was typical of attitudes towards women’s sport for many decades.

Women’s professional sport is now seeing dramatic changes. England will host the 2022 Women’s Euros later this year, and tickets for the final sold out in less than an hour. There is clear demand from fans and not just for women’s football, but other professional women’s sports.

In 2021, 267,000 people attended the women’s matches in English cricket’s new domestic competition, The Hundred, making it the best attended women’s cricket event ever. A year before, another cricketing record was set with 86,174 spectators at the Women’s T20 World Cup final between Australia and India at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. Record crowds for professional women’s matches have also been seen recently in rugby union.

There is increasing investment in women’s sport and a rising number of professional athletic contracts for women. Clubs and organisations are finding that if people know about women’s sport they will attend games and watch it on television.

TV coverage is vital

In a sign that the times really may be changing, the current minister for sport, Nigel Huddleston, and the home secretary, Priti Patel, announced that they are minded to add the (FIFA) Women’s World Cup and the Women’s Euros (UEFA European Women’s Football Championship) to the list of protected sports events. Set out in the 1990s, these are the “crown jewels” of English sport, deemed to be of national importance when it comes to television coverage. The list has not included any women’s events until now, and the proposed change is crucial to keep women’s sport visible for as large an audience as possible.

Football has also seen considerable growth in participation. In 2020, 3.4 million women and girls played football in England and the world governing body FIFA aims to have 60 million playing by 2026.

The wider picture is perhaps less rosy. There are 516,600 more inactive women than men in England. Girls are less active than boys, even though their activity levels increased comparatively during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nonetheless, this pandemic-related increase also points to positive changes. During the lockdowns, there was a shift away from traditional team sports to fitness classes and walking, which have traditionally appealed more to women and girls. In a similar way Sport England’s This Girl Can campaign, which was relaunched in January 2020, aimed to break conventional ideas that physical activity and sport are unsuitable for women. Sport England’s evaluation states that 2.8 million women were more active due to the overall campaign.

With traditional masculine ideals slowly being replaced across society, these changes can also be seen in sport. Sport is also becoming more inclusive for minorities.

And, as happened around 100 years ago, women’s rights and equality in society and workplaces are improving. The #MeToo movement has brought sexual harassment to the forefront of public awareness and is gradually shifting workplace culture.

Threats ahead

However, this is not time for complacency. The pandemic has affected women more than men and in different ways, slowing progress. Greater domestic responsibilities impacted on women’s free time more than men, reducing time for physical activity. Similarly, funding cuts in sport may threaten the gains that have been made in women’s sport. And many males continue to hold unfounded, stereotypical views such as women in sport being more emotional than men.

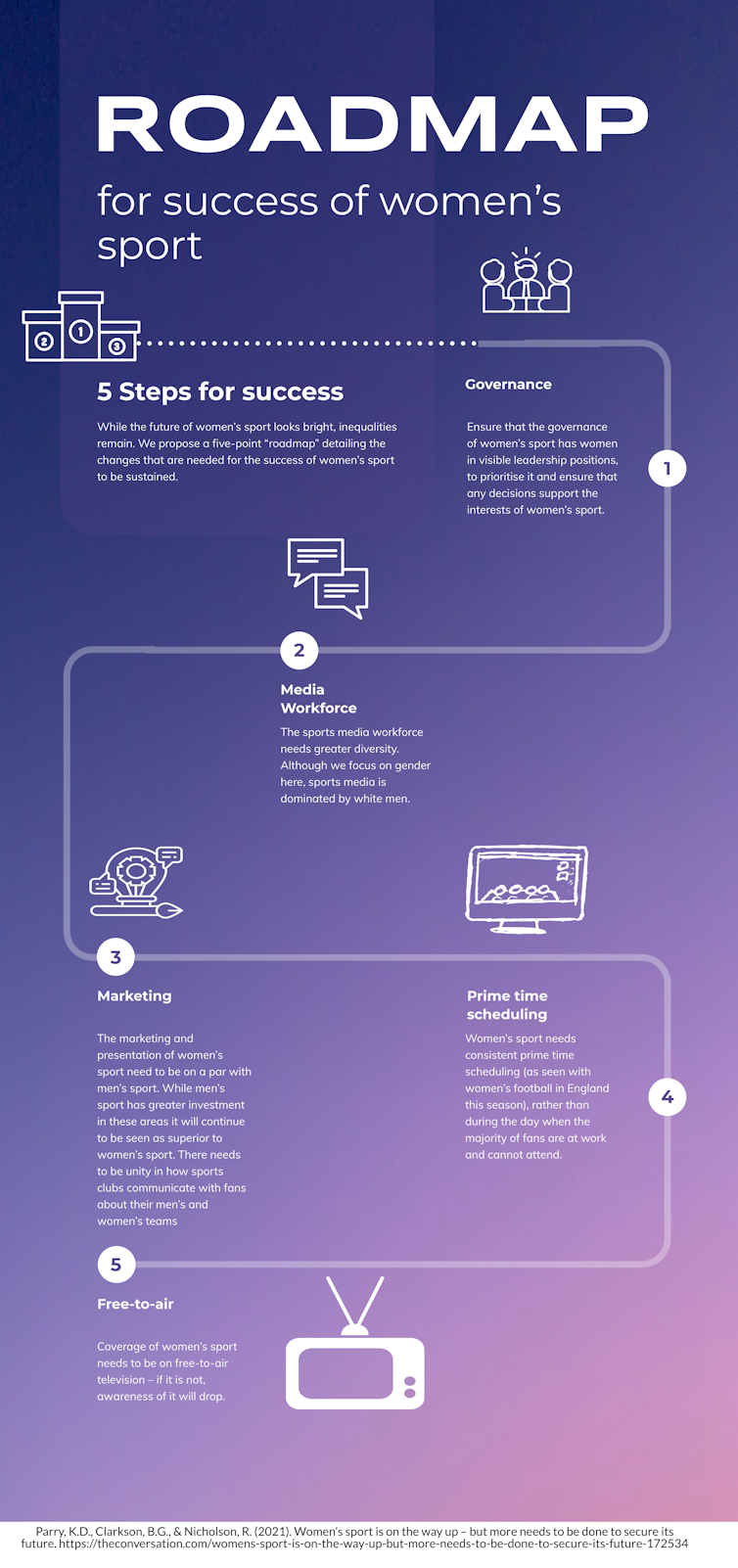

Recently, my colleagues and I mapped out five actions needed to make sure that recent gains for women’s sport are not lost, see below. With changes in society, widespread support for gender equality, and the current popularity of women’s sport, now is the time to act on these changes to ensure that it is not another 100 years before we see the recent attendance records broken. Gender equality is a societal goal and it should be in sport too.

Roadmap for the success of women’s sport

Keith Parry, Deputy Head Of Department in Department of Sport & Event Management, Bournemouth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.