BU's Emeritus Professor Nigel Jump writes the next in a series of economic blogs looking at the impact of covid-19 on the economy.

Levelling Up, Recent Evidence, Fiscal Policy and Ukraine

Levelling Up continued:

My previous blog on Levelling Up (LU) raised some issues, leading me to point out four aspects that may well affect local outcomes:

- The government will identify priority areas for the LU agenda and Dorset is not likely to be one of those. To compete in the ‘market’ for attention and resources, good data and impact evaluation will be crucial. To make a local case, Dorset needs its evidence base to be LU friendly, making key arguments as to where strong ‘returns’ might be expected.

- All high skilled jobs are important, but it will be specific skills that set an area apart. These will make a positive difference to the outcomes of future investment and innovation. For example, all places will need more high skilled medics and/or AI workers. Beyond that, can Dorset provide an (actual and potential) skills base that will differentiate it, in terms of growth and productive performance, from the rest?

- Demand for LU skills is a derived demand. The markets for the sector in which productive skills are applied - the products or services that they produce - are the drivers of positive relative change in growth and productivity. Dorset needs to understand where its competitive and comparative advantage lies, at home and abroad.

- Economic geography does not align exactly with socio-political boundaries. Dorset needs to understand what the right hinterland is for local firms in terms of access to markets, staff and other resources. Dorset is part of a wider LU space for entrepreneurship and competitiveness across south central England. Can it work with other areas, perhaps ones with higher priority in the south west, south central or greater south east?

Recent UK Evidence

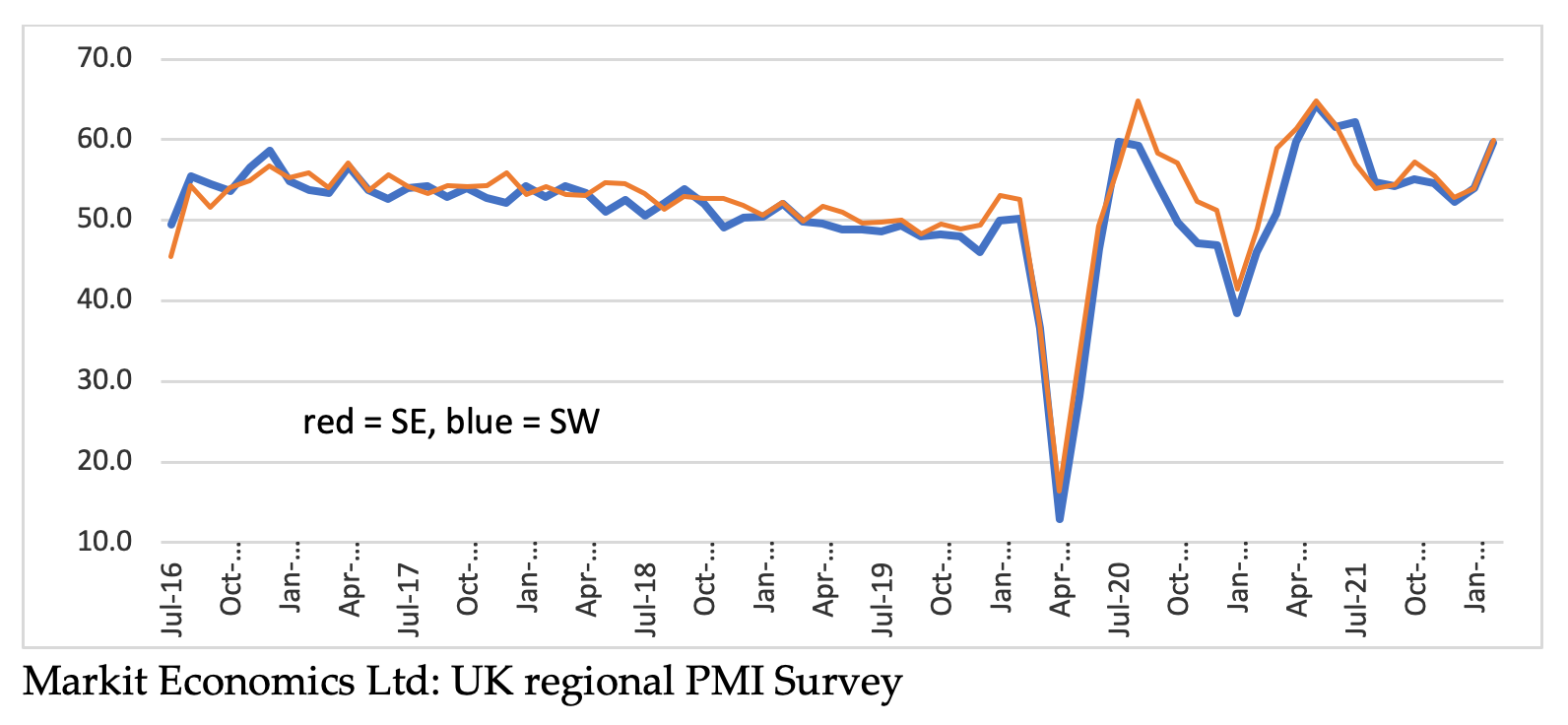

The economy has been volatile recently, with better numbers in one month often followed by a less buoyant one. The waxing and waning of various crises and recent disruptions are focussing attention on short term variability for businesses and households alike. For example, whilst current regional activity indices were stronger in February (see chart below – a Purchasing Managers’ reading above 50 implies growth) the accompanying confidence indicators were weaker because of worries about costs and supply chains.

Virtually all sectors grew in early 2022 – services, production and construction – but there were big gaps between those that are already operating above pre-pandemic levels and those that are still catching up. The recovery persists but prospects are uncertain.

This is reflected in the labour market where unemployment is low (2.8% SW England and 3.8% SE England in the three months to January), vacancies are high and wages for new hiring are increasing. However, these figures mask the fact that many thousands (perhaps, half-a-million) have left the market (become inactive - retired, sick or withdrawn) over the last two years. Skills shortages are not easing.

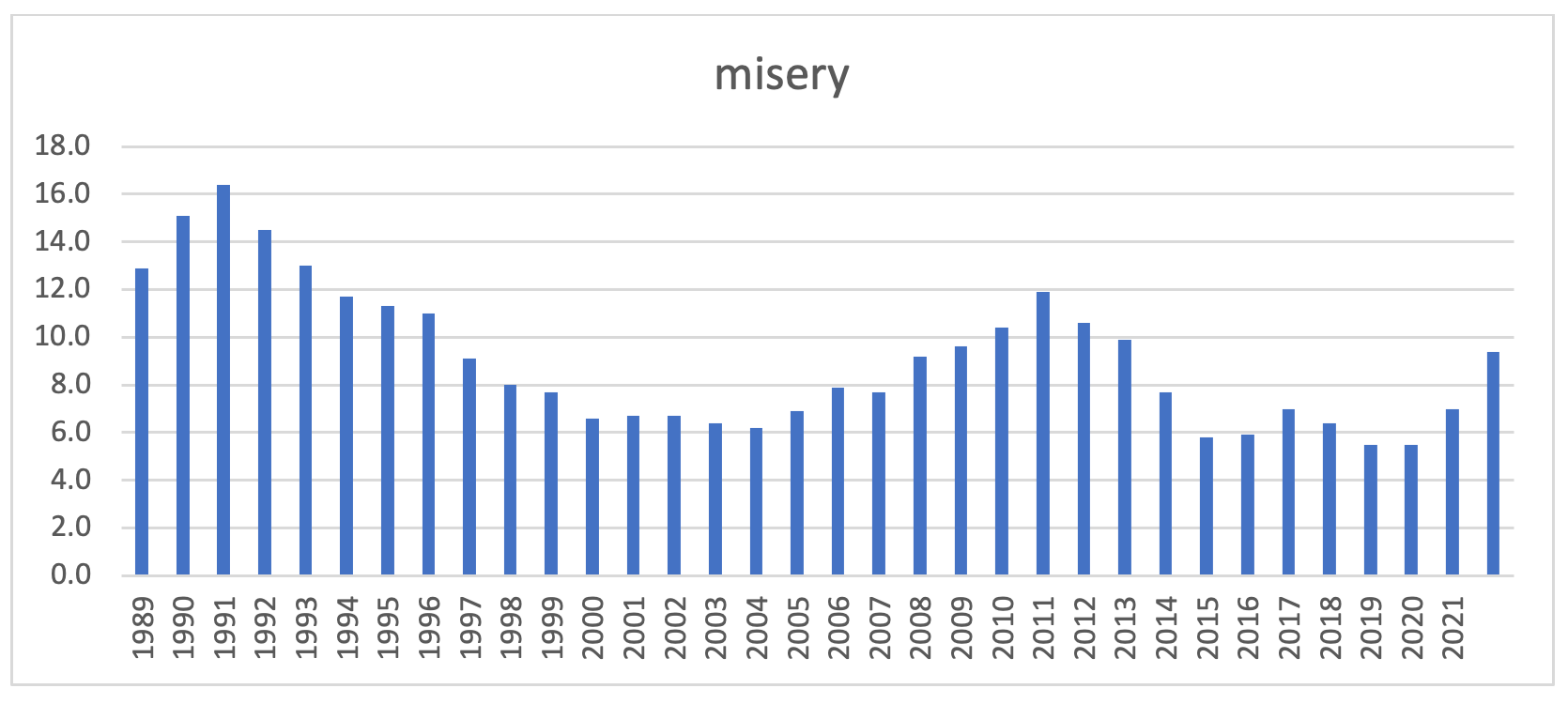

Overall, the Misery Index (inflation plus unemployment as featured in a previous blog) now stands above 9%. This high and still rising rate - see chart below – raises concern about activity levels to come.

The current uncertainty is driven by the impact on household budgets of falling real incomes, debt constraints and rising interest rates. Will emerging pressures on household incomes promote a return to the labour force by those who opted out during the first stages of the pandemic?

The inflation squeeze is going to get worse and financial pressures on consumers and workers will intensify. Also, the trade deficit is widening as trade intensity has narrowed. Global factors, including the effect of the Ukraine war on supply chains and prices (see relevant section below), are at work but the UK situation is made worse by a structural drop in exports, especially to the EU. In the three months to January, UK exports were down 14% compared with an 8.2% rise in the rest of the world – a relative collapse directly linked to Brexit that augurs badly for current and future productivity.

Government Economic Policy

In his Spring Statement (23 March), the Chancellor of the Exchequer talked around the cost-of-living crisis, suggesting the worst is yet to come in the near term. He promoted, however, a Tax Plan for growth and fiscal probity (an income tax rate cut and overall debt reduction) for 2024 and beyond (just in time for the next election).

The Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) reduced its growth (3.8% 2022) and raised its inflation (7.4%) forecasts for now and over the years ahead. In the next year, it expects the biggest hit to real disposable incomes in statistical memory (over 65 years) and the biggest annual debt interest payments (£83bn) ever. Over the next five years, it suggests real growth will seldom reach 2%.

Immediately, Mr Sunak cut fuel duty by 5p per litre, set VAT at 0% (for 5 years) for ‘green’ home energy equipment, and increased household support for fuel poverty through local authorities. He also increased the employment allowance for business.

The Treasury said its Tax Plan aims to help families with higher costs of living, to boost growth potential and to distribute its rewards more fairly.

- From July, for working families, the NI (National Insurance) threshold will increase by £3,000 to £12,570, matching the income tax threshold and halving the impact of the already planned NI rate rise in April. (Does this mean the NHS and Care will now only get £6bn instead of £12bn?)

- For growth and productivity, HM Treasury will consult business on how to incentivise investment in capital, skills/training and R&D allowances. Its conclusions and measures will be announced in the Autumn 2022 budget. (Any of my blog readers will know that positive incentives for skills, investment and innovation are usually “a good thing” for regional development. As always, though, the ‘devil is in the detail’ as to whether any particular policy is effective or optimal.)

- For distribution, in due course, he said inflation and debt will be falling, letting the basic income tax rate be 1p lower, (19p), from 2024.

Whether you approve or not of the government’s overall approach and of its specific measures, they will not stop the negative combinations of trade barriers, Covid-19 pandemic, and Ukraine war/Russian sanctions from raising inflation rates more, and for longer. The Bank of England will have to raise interest rates and tighten quantitative monetary policy more and faster if its target is to be repaired. Whatever the merit of any new fiscal and monetary policies, they are likely to soften confidence, suggesting economic prospects will be weaker than hoped.

Ukraine and Beyond:

The devastation of the Russo-Ukrainian war is appalling, especially for those directly involved (staying or fleeing the area). Putin’s evil crisis will bring damaging economic consequences for us all: many of which are already evident and many that will become noticeable in fairly short order.

- The war affects commodity markets by upsetting the demand/supply balances for foodstuffs (Ukrainian wheat), fuels (Russian oil), metals and other resources, leading to higher inflationary pressures and real shortages across many industries and markets.

- Financial markets have taken severe knocks, with currencies and securities, (stocks and shares, bonds and other debt instruments) all buffeted by down-gradings and sell-offs.

- There are adverse consequences for labour markets and households in specific sectors and places, both directly through some particular jobs and income streams and indirectly through confidence, affecting spending and saving, incomes and living standards.

- There will be supply chain and trade disruptions for some firms, higher cost implications for most businesses and families, with more uncertainty and risks for all, deepening corporate and household caution about forward growth planning.

- Policy regimes will be hamstrung by renewed pressure on fiscal and monetary conditions, especially after the years of pandemic disruption and chaos, and on transformation policies such as green economy and skills investment.

In summary, growth and employment is likely to be lower and inflation higher than it would otherwise have been, especially if the current crises are prolonged. A severe distortion, maybe even reversal, of the whole ‘globalisation’ era is underway. Those of us who remember the 1970s will be aware of the damage this may cause. It is difficult to be sanguine about economic prospects at a time when divisive politics and defensive resilience seem to be regaining ground. The OBR’s more muted macroeconomic forecasts still ride a strong wave of uncertainty.