BU's Emeritus Professor Nigel Jump writes the next in a series of economic blogs looking at the impact of covid-19 on the economy.

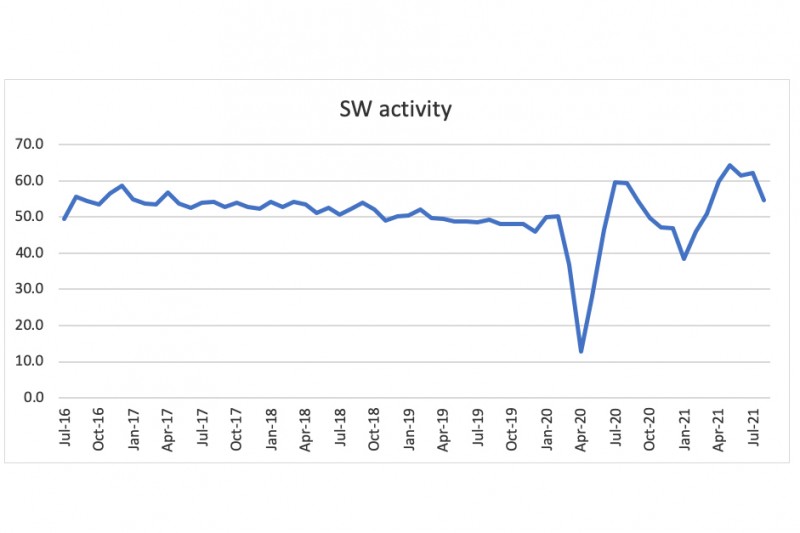

The regional economy grew, albeit at a slower pace, in August and early September, suggesting, in response to various bottlenecks, that the recovery persists but has become less vigorous. Ideally, the purchasing series in the chart below will eventually start to settle down and be less volatile, as it was in 2016/17, (remaining above the 50 reading that indicates overall expansion). This outcome will require, however, greater stabilisation of the pandemic, of sector supply chains and of labour markets.

The danger is that high uncertainty persists for local business as (fiscal and monetary) policy support unwinds, external trading relationships remain disrupted, and important sectors are under-resourced, especially in logistics. The state is playing a larger role in the economy, affecting (crowding out?) private investment and a few consumption patterns more broadly. There is a risk that piecemeal actions are playing catch up, leading to an air of crisis. Moreover, the forthcoming Treasury spending review and tax increases may dampen activity at a time of higher inflation (cost push and demand pull). In due course, tighter monetary conditions (higher interest rates) must come.

For a while, the economy will probably grow because long-term interest rates are low and are likely to remain so for a while, many corporate profits are improving, and nominal GDP should stay robust due to the overly loose monetary policy and demand backlogs. There is some risk, however, to discretionary household (real) incomes and, thereby, consumption and trade. Also, there are supply-side shortages and higher costs to bear, including for energy, manufactures and transport.

Beyond short-term bottlenecks, productive investment is key to future economic success. Investment in infrastructure and skills, fostered by innovation and entrepreneurship, must boost competitiveness locally and internationally. It needs to be driven by increases in relative and absolute productivity through the adoption of technologies and techniques that support the real value of what is created and distributed. This should raise living standards and well-being (now and later, indeed inter-generationally), in ways that are environmentally sustainable. In turn, this means productivity needs to be calculated and interpreted, particularly in cultural and visitor/experience sectors, in ways that reflect value in time spent as well as simply time saved. Around COP26, we need to reassess what prosperity and well-being means for a finite planet.

Government intervention needs to be about supporting natural, human and physical capital in the wider community, whilst minimising financial and real value net leakage beyond the domestic economy. The state’s role is to create the educational, legal, and regulatory conditions that allow businesses and workers to thrive in sustained and sustainable ways. The state is a facilitator and, perhaps, a distributor of last resort, building widespread support for promoting effective fairness in health and welfare, and regional levelling. Meanwhile, through the wealth creation process, local business should apply new productive ideas and methods to building the capacity for, and efficiency of, future markets.

BU’s contribution to a ‘one planet’ economy is

- to undertake ‘blue sky’ and applied research into methodologies and practices for business and regional development and

- to inculcate skills in a labour force, with a community fit that generates the valued and valuable goods and services of tomorrow’s markets.

Recent labour market data suggests the pandemic has not caused as big a rise in unemployment as feared. If anything, jobless rates are falling again. The furlough scheme clearly helped to moderate the labour adjustment, almost acting like a Universal Basic Income. Its removal, however, may yet change these short-term trends sharply and negatively. The recent irony is that furlough numbers remained high in the visitor and leisure sectors, as well as some professions, transport, manufacturing, and construction, yet these were areas where job vacancies and postings have been high. Does this mismatch reflect structural skills gaps in the existing workforce and a need to raise skills levels amongst new recruits?

Other relevant skills factors in need of rebalancing are:

- the role of internal training and work force development alongside that of formal education and professional practice.

- the differences and mismatches between demand and supply for hard and soft skills in the workforce

- the impacts of salary incentives, migration flows, and ageing, on local labour use and recruitment.

Identifying and removing skills gaps and needs for upskilling at a detailed, local level is difficult … but its impact would be profound in tracking and prolonging any genuine, sustained recovery.

Though it has wavered in some areas, the UK government seems keen for market forces to work through, letting shortages and gaps be solved by price/wage adjustments that incentivise shifts in domestic supply (through absolute and relative volumes) rather than by relaxing post-Brexit flows from abroad. It is also vocal in promoting the ‘greening’ of jobs and the workforce – trends that do seem more apparent in the vacant job details currently being advertised. These longer-term trends are vital for future prosperity and, whilst there may be persistent skills disruptions in the near term, they suggest opportunities for skills-led regional development in the years ahead.