BU's Emeritus Professor Nigel Jump writes the next in a series of economic blogs looking at the impact of covid-19 on the economy.

Despite new technology, UK productivity, (as usually measured, such as output per hour worked), has been stagnant for a couple of decades. As a result, the earnings distribution has become more unequal. Firms have been shedding workforce, but not making the most of AI and other new technologies to boost output. The significant implementation lag between new ideas and their broad economic application, use and acceptance has been evident. The chain from productivity, through profits and jobs, to wages has not been working well.

As international wage differentials have narrowed (and been less of a driver of locational investment decisions), there has been some ‘onshoring’ but overall uncertainty has increased. The pandemic has made the slowdown of investment seen after the 2008 finance/debt crisis, (and later reinforced by the Brexit referendum), worse. Moreover, world trade is no longer leading the growth process. Globalisation is making a smaller contribution to growth as the desire for domestic resilience increases. In the years ahead, these influences will affect the distribution of activity and wealth … for good or ill.

Against this background, government economic policies should aim to build incentives for innovative human and physical investment, thereby fostering comparative and competitive advantage. Higher productivity and the link through to wellbeing requires investment in new things and new thoughts. Growth must not simply replace unproductive workers but also release skills for ‘new’ activities and ‘better’ jobs.

The trouble is the pandemic leaves government with large debts to service. The burden is not unprecedented (see 1950/60s). Moreover, low real interest rates make it fairly easy to service in the short term, (especially if you are borrowing in your own currency). How long, however, will interest rates stay low in the face of higher inflation expectations? The ultimate question is who pays for the debt and when? Hopefully, it can be paid for by positive restructuring and growth that reduces economic scarring and drives productivity. More negatively, however, it can be paid for by low real interest rates (a tax on savers), higher inflation (a regressive tax on incomes) and/or by higher direct taxes and lower spending (more fiscal austerity).

Current uncertainty about the future reflects the economic scarring from the pandemic. Scarring is evident in three broad forms:

- low investment, meaning a smaller capital stock to promote productivity-led growth.

- lower labour supply, meaning permanently higher unemployment levels, accelerated early retirement and lower net immigration.

- lower absolute productivity, meaning weaker infrastructure and skills, subdued innovation, and entrepreneurship, and a loss of competitiveness (Brexit).

It is not yet clear whether the pandemic means a major structural change. But it does suggest, at least, some difficulty in acquiring the resources to redress the productive deficiencies, especially given the need to raise and spend more £-billions for ongoing vaccination and track and trace efforts, and for education and health catch ups.

The 2020s are going to be a difficult and interesting decade as we try to overcome the wounds and scars of the last decade or so, raising the productive performance of a weakened economy whilst reducing carbon emissions. Applied and ‘blue sky’ research and more-targeted training and general education are likely to be the key ingredients of success.

- Universities, including Bournemouth, have an important role in promoting the process of economic renewal through innovation and skills.

- State agencies (LEPs plus) and local authorities have a key role in supporting long-term development of infrastructure and competitiveness, including climate change incentives.

- Businesses has a vital role in responding and making improvements in resource use and corporate investment through new and strong entrepreneurship.

- Workforces have a special role in fostering flexibility, training and adaptation.

Risk and difficulty abound but, with the right attitude of ambition, so does opportunity and initiative.

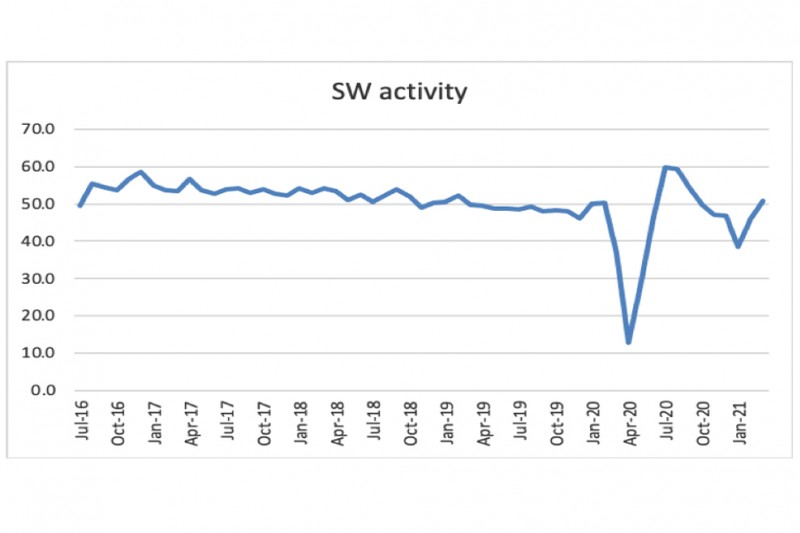

Meanwhile, in 2021, the anticipated W-shaped recovery in the regional economy is playing out pretty much as expected (see chart below). With more activity potentially opening up for a more optimistic and vaccinated population, activity looks set to be more positive (above 50 on this PMI index in March) with economic growth through Q2 and Q3. Hopefully, personal and state measures to avoid another end-year covid19 wave will maintain higher activity levels and recovery growth beyond the summer.