BU's Emeritus Professor Nigel Jump writes the next in a series of economic blogs looking at the impact of covid-19 on the economy.

CURRENT SITUATION

The latest figures show unemployment and inflation rates both rising: the former moving to 4.8% (3 months to September) and the latter at 0.9% (CPIH, year to October). We are not at ‘stagflation’ yet, but the risk of heading that way is increasing: several commentators predict something like 7%+ for unemployment and 2%+ for inflation within the next twelve-to-twenty-four months.

In its latest analysis (released 25th November), the Office of Budget Responsibility forecasts a fall in real GDP of 11.3% this year, with a rise by 5.5% in 2021 and 6.6% in 2022 before dropping back to ‘normal rates’ of growth (2% or less). The previous peak of national output is said to be regained in Q4 2022 and, by 2025, the economy is still 3% below what it would otherwise have reached without Covid19. Unemployment is said to peak at 2.6mn next year, a rate of about 7.5%. Inflation is not predicted to reach 2% until 2025!

Meanwhile, government borrowing is set to reach almost £400bn this year (fiscal 2020/21) – some 19% of GDP, and still to be at about £100bn per annum (4% of GDP) at the end of the forecast period. Public sector net debt climbs from over £2.2trn this year to £2.8trn in 2025/26. It peaks at about 110% of GDP and stays close to 100% throughout the period. Such numbers are enormous and unprecedented in peacetime. The big question is how we address and pay for this over the long run – through a combination of growth, inflation or austerity. What if world interest rates rise, what if recovery/growth stalls, what if further shocks are encountered?

Successful vaccination, track and trace and distancing might yield a better-than-expected recovery in 2021. This might cap the unemployment rate but boost price momentum. Alternatively, a weak recovery might subdue inflation and raise unemployment. Either way, a period of combined ‘stagflation’ is possible.

CURRENT PROSPECTS

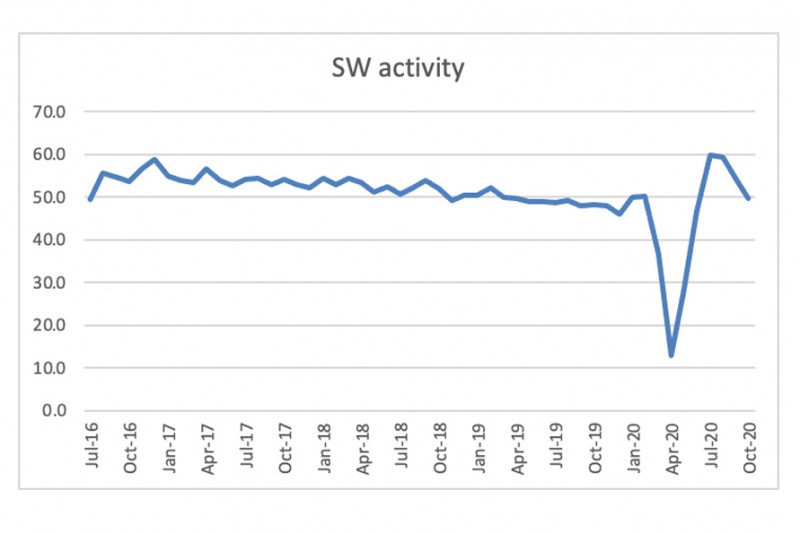

In the short term, a W-shaped recovery has become more likely. UK real GDP bounced up 15.5% in Q2 2020, but its level was still almost 10% down on the Q4 2019. Q3 ended softly and Q4 is reflecting the second lockdown. The chart below is starting to show this W-shape. Importantly, these readings are not absolute indicators but are measures of current momentum: the level of about 60 in Q3 2020 does not mean a higher level of output than before the pandemic, it means a more widespread bounce from the Q2 low.

Also, note that the index was already shifting below 50 in 2019 – well before the first pandemic lockdown. Over a year ago, an underlying economic weakness was already emerging. Sadly, this regional output indicator slipped back again to 49.7 in October. More slowing is expected for November’s second lockdown, drawing out a second trough for the W-shaped growth path. Moreover, the lockdowns across Europe and America will restrict Q4 output more generally, with increasing demand and supply constraints. A renewed upturn in 2021 is often predicted, especially after the recent positive vaccine news boosted some financial markets, but its scale and timing remain uncertain.

SW PMI (July 2016 – November 2020) Source: IHS Markit for NatWest. Remember, for this SW PMI measure, any reading below 50 implies regional economic contraction and above 50 signals expansion.

Against this background, the Chancellor’s latest Spending Review (also 25th November) incorporated a number of spending commitments to support a growth recovery, including larger sums for defence, health, education, R&D and infrastructure. There were no major tax announcements, but several “kites have been flown”, especially higher taxes in the medium term, perhaps on capital gains, inheritances or even main incomes and sales (VAT). Also, there is pay restraint for parts of the public sector to “share” the pain with private sector redundancies/wage falls as caused by the pandemic.

So, there are major, short term issues about the path of the economy but here I want to focus on the longer term matter of productivity. The UK’s underlying economic problem is its lack of productivity growth and its low relative productivity level compared with our competitors. Throughout the 2010s, UK productivity performances - measured as output per worker, per hour or per job - were weak, at best. UK performance slipped down the league of G7 results and is about a third below US levels and 10-15% below Germany and France. The Covid19 pandemic has made this worse. In Q2 2020, UK output per worker was more than 20% below its year ago level.

Productivity is important because it is the source of all wealth and economic progress. Productivity creates value (what you get out is more than what you put in). By raising profits and wages in the more productive activities, the created value can be used to satisfy peoples’ needs and wants, sending signals as to where resources can be best applied. Over time, the extra value created by higher productivity can be used to improve resource allocation and social well-being, providing funds for the services and products we desire and for addressing negative aspects of human activity (such as poverty, environmental degradation and fairness).

The UK’s poor productivity performance reflects a number of measurement and behaviour issues. Key among these is that the output statistics (numerator of productivity) tend not to cover the economy’s whole balance sheet (e.g. not reflecting environmental externalities and full consumer surpluses). Also, the input statistics (denominator) is not always good at measuring natural capital and skills. Productivity needs to be used appropriately with analysis of associated distribution/equality/green issues.

- First, it’s harder to measure a) digital productivity than manufacturing productivity; b) hours worked in services rather than factories, especially in an era of more home working; and c) modern capital per worker – what people use with their labour to add value, particularly as capital use and definitions have become more intangible. For example, it is often more difficult to quantify asset lifespans for many modern technologies.

- Second, UK business investment is poor – (flat since 2015 and worse this year) - and management practices can be weak – (long tail of ‘zombie’ companies and workers with low productivity).

- Third, some allocative changes are not helping – e.g. the relative decline in North Sea oil’s share of UK output demotes comparatively high productivity activities which have been replaced by lower productivity activities.

The odd thing is that the market is not addressing these issues as our textbooks would predict. It is the persistent nature of UK’s poor productivity performance that is most alarming. Why have ‘good’ profitable firms with high skilled labour not competed out ‘bad’ ones?

The government’s spending plans can affect productivity by boosting infrastructure, encouraging ‘good’ firms and reallocating from ‘zombies’, and by encouraging investment in better human, environmental and physical capital. The latest one-year spending review promises a number of things related to this. In particular, it supports regional economic development by creating an Infrastructure Bank (to be set up in the north), a Levelling Up Fund (£4bn) and more for skills, housing, R&D, and capital spending.

No doubt, Dorset’s development actors will be angling for a decent share of these initiatives and financial resources in the weeks and months ahead. But, be warned, previous such policies have floundered in short-termism and poor execution. A lasting productivity dividend – the only source of future sustainable prosperity, requires a consistent and market supportive approach. It needs strong strategy, best practice policy and superb delivery. It requires efficiency and efficacy, co-operation and persistence, and an openness to company, workforce, behavioural and technological change. My long years in the field of local economic development make me cautious, perhaps somewhat sceptical, but the hope must be that this time things are different.