BU's Emeritus Professor Nigel Jump writes the next in a series of economic blogs looking at the impact of covid-19 on the economy.

CURRENT SITUATION

The second quarter of 2020 (April-June, Q2) will be the worst for UK economic growth of any previously experienced by the vast majority of people alive today. It will see something in the region of a 10-25% decline in GDP (-20.4% in April).

The supply-side shock caused by measures taken to address the Covid19 pandemic led to a demand shock of lower consumer and business spending.

- On the supply-side, businesses cut production and re-aligned supply chains. Some sectors were effectively closed. Many workers stayed home and worked, produced, and earned less than usual.

- On the demand-side, uncertainty increased about household incomes and employment, and corporate investment and trade. Confidence fell, encouraging precautionary saving and reducing discretionary spending: current consumption decreased in many sectors (especially personal services).

- On prices, with aggregate demand falling more than potential aggregate supply, disinflation (slower but still positive, average inflation) occurred. Again, there were significant sector differences (e.g. some foods up, some fuels down).

- On policy, governments added offsetting and unprecedented (monetary and fiscal) stimuli and guarantees, reinforcing feeble automatic stabilisers (lower taxes and higher spending in recession).

Globally, financial withdrawal has taken many forms and exacerbated the malaise.

Locally, there is supported anecdotal evidence of many firms shutting down in April and experiencing only a modest improvement in May and June. (The SW PMI activity index from Markit/Nat West was just 28.1 in May, less negative than in April but still signalling a marked contraction.)

Meanwhile, the labour market has contracted, with the number of UK employee payrolls down over 600,000 in the latest period. May’s claimant count rates rose sharply (to 4.8% in Dorset up from 1.8% in January and 6.6% in BCP compared with 2.5%). National vacancies are at a record low (-60%). Many more people are temporarily out of work: including those furloughed. There has been a big drop in working hours and a fall in real, average pay.

CURRENT PROSPECTS

The economic outlook depends on the epidemiological progress of the pandemic and the economic policy and behavioural response to the recession.

Epidemiology question: will the easing of the (first) lockdown and potential mutation of the virus before winter create a new (second) phase and threaten renewed lockdown, … or not?

We need effective treatments for the sick and a vaccine to create herd immunity. Whether or not you think action-to-date has been appropriate and timely, government strategy is to buy time until prevention is good and the economy better. Health policy aims to reduce the spread of the virus, given demographic susceptibility and immunity, by limiting transmission through reduced contact and increased hygiene. The problem is we still do not have enough knowledge of or control over many of these disease factors. The UK’s infection and death rates, though falling, remain relatively high.

Policy question: will the aggressive public support (fiscal and monetary) injections worth several £100bn of state spending, borrowing and QE be enough to manage a second wave of economic disruption and decline, … or not?

If aggregate, negative supply effects exceed the negative demand effects, inflation accelerates. If demand contracts more than supply, (as right now), inflation decelerates (CPI down to +0.5% in the year to May). The longer the economic crisis persists, with a weak and unstable recovery and deep troughs, the more likely it is that government will:

- a) seek to inflate away the financial burden through prolonged (excess) monetary expansion with, perhaps, direct cash handouts (‘helicopter money’);

- b) find it hard to continue the counter-depression fiscal measures.

The Treasury is hoping that its special measures (direct budget, indirect commitments and guarantees, including a putative VAT reduction) are temporary (offset, clawed back or reduced as the economy rebounds) and affordable (current interest rates mean low borrowing costs).

Neither of these assumptions or conditions are guaranteed to last. UK debt reached £1.95trn in May, more than annual GDP for the first time since 1963. The deficit is at record levels. Given the pandemic, such a shift into high debt ratios is understandable (and repeated around the globe) but it still represents a burden to future tax payers that will probably restrain growth for years to come – just as post-WW2 debts curtailed the UK economy for a decade or so.

Behavioural question: will household and business confidence bounce back (releasing pent up demand) or remain cautious (fearing for jobs and incomes)?

Some discretionary spending will be lost forever (especially services, including elements of leisure and hospitality). Some cutbacks will be amplified by reassessment of globalisation in industrial supply chains. Unfortunately, we are going through the crisis with corporate and public debts already high. Banks are less stressed than in 2008/9 but ‘bad debt’ ratios are vulnerable to hysteresis (long term damage to business resilience (capital/investment) and the impact of firm closures and unemployment on creditworthiness. At some point, slugs of the monetary and debt overhang are likely to be monetised.

Future Scenarios: The initial disinflationary impact will probably persist this summer, whilst the demand shock is worse than the supply shock and the output gap (difference between potential and actual output) remains wide. Moreover, after Covid19, companies are in a worse position to deal with an adverse/no Brexit deal for 2021 onwards. Britain’s poor relative performance on Covid19 has shown its vulnerability to working alone in terms of doing deals with, and acquiring necessary resources from, its large partners (EU, America, China et al).

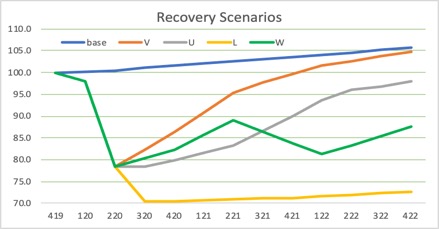

We can envisage three broad possible futures:

- Rebound: higher unemployment and inflation with only moderate output growth (U shaped recovery).

- Collapse: deflation (negative inflation) and recession (negative growth) persist into a lengthy depression (L shaped recovery).

- Bounce: pent up pressure reignites demand, output climbs and prices accelerate (V shaped recovery).

In a ‘worst’ case, the ‘misery index’ (the sum of the unemployment and inflation rates) could return to the highs of 15-25% last experienced in the 1970s (perhaps 10-15% unemployment plus 5-10% inflation).

Even under a ‘best’ case, ‘misery’ could well increase towards 10% (7-9% plus 0-2%), compared with a ‘normal target’ of about 6% (3-4% plus 2%).

Given the higher than usual uncertainty, there is little consensus on the probabilities attached to any current forecast. In these circumstances, economic models driven by calculus equations, at best, are even more imprecise and, at worst, break down. Moreover, the underlying assumptions have to be heroic. For what it’s worth, I have seen probabilities of 40-50% ascribed to U and 25-30% each to L and V. Effectively, no one knows.

- A U-recovery (rebound) means a gradual improvement in the supply/demand balance as the pandemic slowly recedes. This modest upturn gets underway in the second half of 2020 and gathers some momentum in 2021. Output does not return to pre-Covid19 levels for at least 18 months. Unemployment rises and there is some long-term productive scarring, but not disastrously or permanently. Inflation remains positive but low. Policy remains ‘loose’, but slowly (over several years) adjusts towards something less accommodating.

- An L-recovery (collapse) means much higher unemployment later this year and beyond. Concerns over long-term deflation increase. Policy remains very ‘loose’ and is not expected to move to a better balance for the foreseeable future. Its impact, however, is partly exhausted. Supply constraints solidify and demand incentives soften worryingly. The economy stays depressed and the pandemic persists as a major economic constraint.

- A V-recovery (bounce) means the pandemic is controlled sooner than now expected, demand bounces back and encourages supply, softening the uptick in unemployment and encouraging inflation. Financial markets and governments start to anticipate a return to a more sustainable policy mix and a good corporate recover.

Q4 2019 GDP = 100, Q1 2020 already known (-2%), Q2 2020 = expected, rest are figurative scenarios rather than modelled forecasts.

These ‘letter’ scenarios merely act as references against which to assess developments as they arise. In practice, given unprecedented times, some obscure combination of these different patterns may well occur; perhaps something more W-shaped with various ups and downs, periods of temporary relief, false starts and blind alleys. It is likely that the economy’s eventual upward path will remain below what might have occurred without the pandemic (see chart above, which shows schematically, in index form, how the GDP ‘letters’ might relate to a non-pandemic base over the next 30 months).

Future Development:

Victor Hugo is translated as saying, “For the weak, the future is unattainable; for the fearful it is unknown; for the courageous, it means opportunity.”

In his inaugural speech in 1933, during the Great Depression, F.D. Roosevelt said, “The only thing we have to fear is ... fear itself — nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”

It is easy for business to ‘freeze’ when faced with a highly uncertain future. To face major change, economic actors need to remain psychologically and physically active and to remember the basics. In economic development, the basics are founded on a few main drivers of growth and productivity.

- For labour and capital, (and natural resources), the future belongs to sustainable and sustained investment in new capacity, technologies and skills, as well as maintaining open markets.

- Government needs to provide the incentives (through infrastructure, prices and taxes) to encourage positive renewal.

- Business and households must capture and use those incentives through productive innovation and entrepreneurship.

- Business success depends on identifying competitive opportunity and exploiting comparative advantage, even in difficult times.

Over time, many details of the human, economic story change but the fundamental basis of economic progress does not. Steadily evolving (perhaps significantly after the Lockdown Recession), it is about what is valued and how we capture and distribute that value, supporting social (community and individual) well-being. It is about individual and corporate psychologies and actions in response to broad political and social incentives.

Whatever its ‘letter’ shape, the Lockdown Recovery may question the stark efficiency of economic globalisation and place more emphasis on social and environmental resilience. Local firms and workers can prepare for that even as they trawl through the near-term crisis.