A Bournemouth University archaeologist has helped to uncover the mystery of a lost World War II vessel.

A collaboration between a team of marine scientists and technicians based in the School of Ocean Sciences at Bangor University, working with internationally renowned nautical archaeologist and historian Dr Innes McCartney from Bournemouth University has resulted in the unexpected discovery and identification of a landing craft which was mysteriously lost at sea during WW2.

Multibeam sonar data collected from a known shipwreck site off Bardsey Island by the Bangor team using the research vessel Prince Madog in 2019 has recently been identified as a World War 2 landing craft reportedly lost off the Isle of Man.

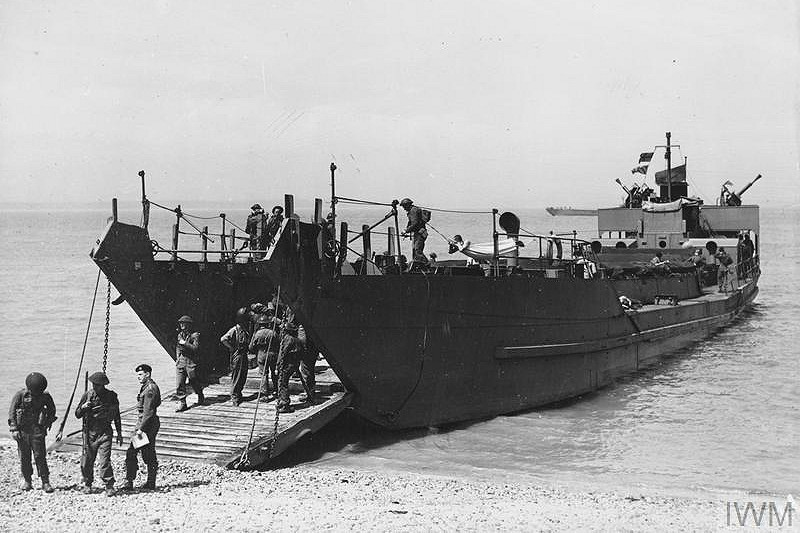

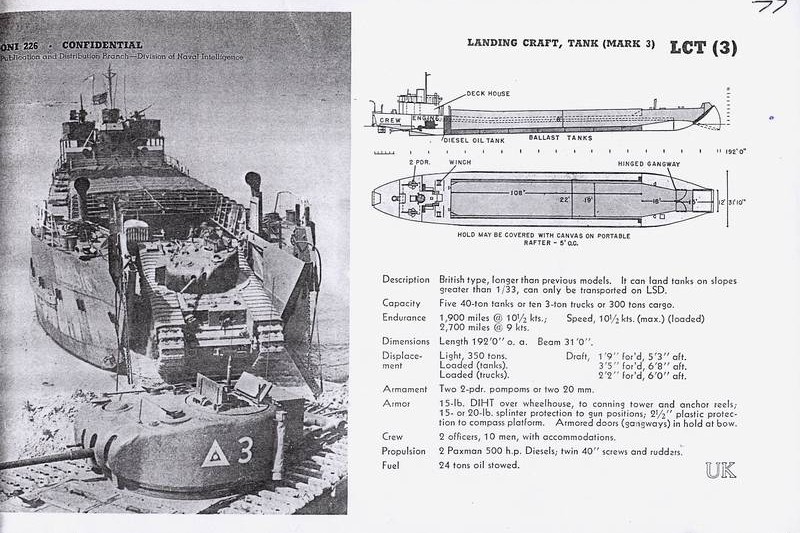

LCT 326 was an Mk III ‘Landing Craft Tank’ designed to land armoured vehicles during amphibious operations, she was built in Middlesbrough and launched in April 1942. These highly specialised vessels were built in large numbers in the last years of WW2 and were extensively used during the D-day operations of June 1944. LCT 326 disappeared while transiting from Scotland to Devon in February 1943 with the loss of fourteen crew and the Admiralty listed the cause of the loss at the time to bad weather or collision with a mine off the Isle of Man, however this new research now places the wreck over 100 miles away off Bardsey Island, North Wales.

Dr Innes McCartney said: “The wreck of LCT 326 is one of over 300 sites in Welsh waters which have been surveyed by the Prince Madog and the aim of this particular piece of research is to identify as many offshore wrecks in Welsh waters as possible and shed light on their respective maritime heritage. This aspect of the project has resulted in many new and exciting discoveries relating to both world wars, of which LCT 326 is just one example.”

The sonar data will also play a pivotal role in helping develop the offshore renewable energy sector in Wales via the Bangor University led SEACAMS2 research project, which is examining the effect that shipwrecks have on the marine environment.

Lead researcher Dr Michael Roberts said: “Establishing the identity of these offshore wrecks and thereby determining how long they have been submerged is crucial in helping us understand how structures interact with marine processes on timescales that are of great interest to the marine renewable energy industry.

“Wrecks such as LCT 326 and their associated physical and ecological ‘footprints’ can often provide us with preliminary insights on the nature and properties of the surrounding seabed without having to undertake more complex, challenging and expensive geo-scientific surveys.”

Initial analysis of the sonar data obtained from the site, including the wreck dimensions and general appearance suggested the wreck was an LCT, further archival research identified the remains as most likely being LCT 326.

Documents in the National Archives show that the ship was part of the 7th LCT Flotilla and was on a transit cruise from Troon, Scotland to Appledore, Devon. The flotilla, under the watch of HMS COTILLION set sail on 31st January 1943. According to records at the time the weather was ‘heavy’ and the flotilla made slow progress south. The flotilla passed the Isle of Man at daylight on February 1st and continued south, that evening at 1830hrs as the weather freshened again, HMS COTILLION made a check on the flotilla and observed that LCT 326 was still with the convoy. That was the last time LCT 326 was seen, crucially, the position at which this check was made was recorded as being just northwest of Bardsey Island.

The wreck has now been identified as being located in a position 25 miles further south from where LCT 326 was last seen and in near-perfect line with the flotilla’s course lying in over 90m of water. The dimensions and appearance of the wreck from the sonar data show that it is 58m long and 10m wide, which is similar to the dimensions of an MKIII LCT. The wreck is shown to be in two halves, lying on the seabed 130m apart.

This vessel appears to have foundered in heavy seas sometime after it was last seen and probably broke in half just forward of the bridge, with both halves staying afloat long enough to have become separated by 130m. The sonar data clearly shows key features of the vessel such as its distinctive landing gangway and stern deck house and although the cause of the loss of this vessel remains unknown (mine explosion or collision cannot be absolutely ruled out) the evidence suggests this may have been nothing more than a tragic marine accident.

The location of this naval grave will now be reported to the Admiralty, so that the records can be corrected and the resting place of the 14 crew accurately recorded.

‘Echoes from the Deep: Modern Reflections on our Maritime Past’ is funded by the Leverhulme Trust and will be published in 2021.