India's economy: how the world's fastest growing nation went off the rails

Not first class. happystock

Not first class. happystock

Sangeeta Khorana, Bournemouth University

India celebrates the traditional harvest festivals of Bihu, Pongal, Makara Sankranti and Lohri across different states in the second week of January. The festivities have become lavish in recent years as the economy has enjoyed high growth rates. But change is in the air.

India’s GDP was growing at between 7% and 8% for the past few years, the fastest rate in the world. But in the last year it has been decelerating markedly: the growth rate slumped to 4.5% in the third quarter of 2019, the slowest in six years.

The IMF, World Bank and OECD all sounded the alarm in October after the Reserve Bank of India trimmed the country’s projected growth rate to 6.1% for 2019-20. This was on the back of a sharp decline in private consumption and weakening growth in industry and services. Despite numerous cuts to interest rates in 2019, the central bank again cut its forecast in December, this time to 5%. So what is going wrong, and where does India go from here?

Economic woes

A host of factors have contributed to India’s economic malaise. When Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) party was originally elected to run the country in 2014, it inherited a weak banking and finance sector saddled with too much bad debt and serious problems with fraud. This had made lending more difficult and triggered declines in consumer spending, business investment and exports.

The government has made reforms such as providing the banks with extra capital, introducing new bankruptcy rules to give extra protection to lenders, and consolidating the state-owned institutions that dominate the sector. Nonetheless, the banks remain fragile, amid a perception that the reforms have not been aggressive enough.

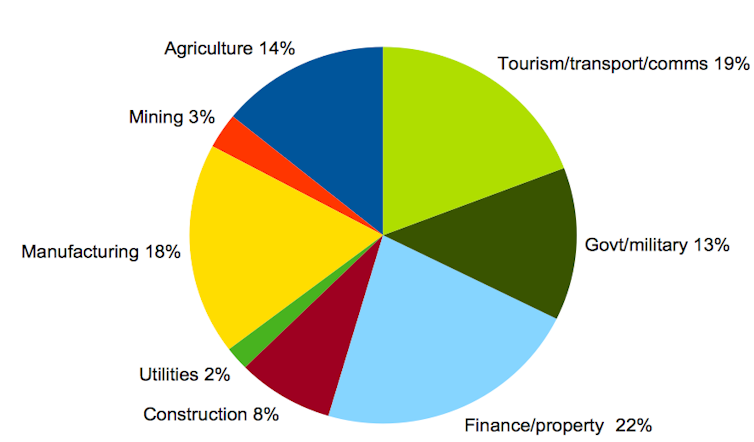

India’s economy

In the face of this problem, much of the demand for credit has been picked up by the so-called non-banking financial corporations. They are now responsible for about a fifth of all lending in the country, but they have been through turbulent times themselves lately, having become over-extended and due to problems with their funding model. This has made it harder for people to get loans for vehicles and mortgages. One knock-on effect has been a slump in the residential property market. Once again, the government has stepped in to recapitalise these institutions.

At the same time, Modi’s plan to raise the economic contribution of manufacturing from 15% to 25% of GDP is not making much progress. The flagship Make in India initiative, which aims to attract more manufacturing contracts from foreign companies, has produced disappointing results.

It has partly been held back by other BJP reforms such as the goods and service tax (GST) system introduced in 2017, which has been cumbersome and unfriendly to business. It requires companies to file separate returns for every state in which they have a presence, for instance. State governments agreed several years ago to reduce the tax burden in certain categories after coming under fire from business leaders.

Manufacturing football equipment at Jalandhar in north India. EPA

Manufacturing football equipment at Jalandhar in north India. EPA

India’s lacklustre performance has also been aggravated by the global economic downturn and ongoing international trade disputes between the US, China and the EU. In a climate of growing protectionism, India’s exports have declined. The country’s current account deficit, which is the measure of imports vs exports, widened from 1.8% in 2017-18 to 2.1% in the most recent year, the highest in six years.

Meanwhile, unemployment has soared. It hit an all-time high of 8.5% in October 2019, with the labour participation rate falling to barely half of adults. There are mounting concerns that this could lead to political instability.

What next?

The solutions to India’s economic crisis are unlikely to be straightforward or speedy. When the IMF and others raised concerns in October, they weren’t just reacting to the slowdown. They were questioning the quality of growth, which included very little private sector investment and was flattered by cheap oil imports; and they were also calling for long-term structural reforms to make the country more efficient and less dependent on the state.

Modi, who was re-elected as PM in 2019, has initiated various reforms in recent months. These include lowering corporation tax rates from 30% to 22%; slashing corporation tax rates for investments in greenfield manufacturing plants to 15% from 25%; raising foreign direct investment restrictions in a range of sectors; and sanctioning reductions to interest rates. His administration has also successfully cut red tape, which has seen India climb from 134th to 77th in the World Bank’s rankings for ease of doing business.

So far, this has failed to invigorate the economy. The current labour and land acquisition laws are archaic and need addressing urgently to rebuild business confidence. For instance, manufacturing firms that employ more than 100 employees have to obtain official approval before making staff redundant, which makes it difficult for firms to improve productivity and adapt to innovation.

The government also needs to go further in improving the banking sector, including stricter regulations over lending and enhanced supervision from regulators. Until such matters are addressed, it is difficult to see India living up to its vast potential.![]()

Sangeeta Khorana, Professor of Economics, Bournemouth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.