It is now a year since BU started providing these economy blogs to those interested in local business and sector development. In that time, we have covered a range of issues, including recession and recovery; productivity, trade, growth and inflation; values and choices; flows and assets; inequality and environment; monetary and fiscal policy; and other principles of local analysis.

The past year’s events and policies have been unprecedented. The global shut down disrupted supply chains, stressed businesses and services and displaced workers. Governments have responded by printing and borrowing money, masking the pain but not mending the wounds. Government and business now need to refocus on generating real wealth from the supply side rather than further stimulating demand.

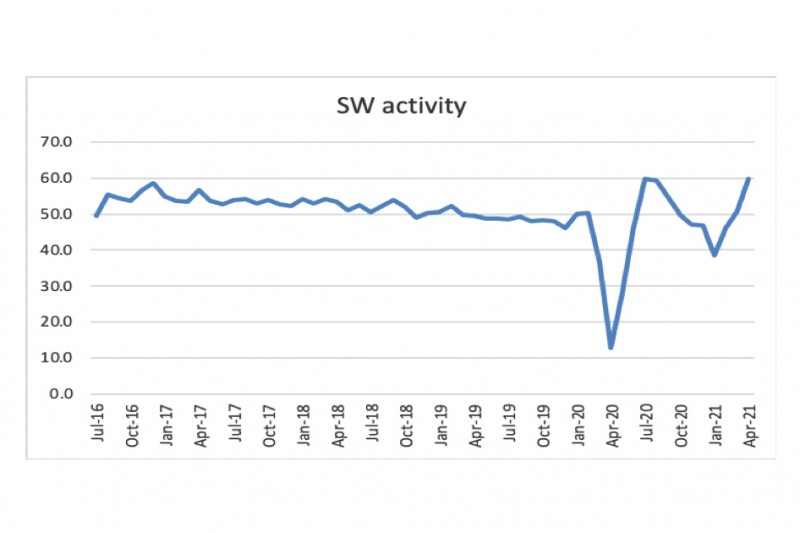

The year of pandemic has seen some of the biggest swings in economic performance ever experienced by local households, businesses and agencies. The W-shaped path of recession and recovery (see chart below) has involved considerable uncertainty and behavioural change. So, where do we stand in mid-2021 and where are we headed?

First, after shrinking 10% in 2020, UK real GDP was 1.5% lower in 2021 Q1 than in Q4 2020, as the third lockdown and Brexit dealt a blow to domestic and export activity respectively. Assuming the pandemic is now waning, thanks to a successful vaccination schedule, forecasters expect the UK economy to grow by about 7% in 2021. (April’s retail sales volumes already suggest a Q2 bounce.) This is quite a surge, but it does not mean a full return to the pre-downturn position. (Industrial production remains below the pre-Covid peak of February 2020). That will take longer – maybe well into 2022. Also, it does not mean all losses will be replaced. Some of the impacts of the deliberate shutdown will be permanent – for good, more efficient working practices and supply chains, and for bad, loss of capacity, jobs and skills.

Second, there are risks to the balances between productivity, unemployment and inflation, with fears that growth of productivity will be too weak, unemployment will adjust more (latest 4.8%, three months to March 2021), and inflation will accelerate. Productivity has not grown at a reasonable rate for many years, hidden unemployment looks to be significant and, whilst inflation is still below target (1.6% CPIH in the year to April), the pressures from excess monetary growth (demand pull) and commodity/supply chain prices and capacities (cost push) are intensifying. At the same time, we see contradictory signals from the labour market as demand and supply adjust to changes in behaviour and incentives. Some sectors (such as parts of the visitor economy and haulage) face difficulties in attracting skilled staff as they open up while others (including perhaps some of those boosted by the pandemic) face the need to re-adjust to ‘normality’.

Third, there is uncertainty about present and future structural changes and aspirational deficiencies for infrastructure, other investment, skills, entrepreneurship and competitiveness. Ultimately, there is no ‘’free lunch”, extra government spending today means reduced spending by others at some point. Positively, there may be "good" infrastructure projects and other interventions out there that will more than pay for themselves. Negatively, parts of current expenditure represent substitution, displacement and diversion rather than a net gain to long run activity. Some of the disruptive structural effects of the pandemic are yet to feed through to underlying capacity and performance.

Fourth, the policy world is shifting. Whether it is the usual stabilisation areas (money supply, interest rates, public spending and taxes) or in non-cyclical change (climate change, new technologies, local levelling up, and external trade and relations), a period of major structural adjustment appears imminent. In the best of times, this amount of change can dampen current activity in return for future gains. In the worst of times, the process of transformation can be precarious and long lasting. It will be some time before we know what the next balance will be.

Meanwhile, the W-shaped rebound is clearly on. As the chart shows, the SW activity index was nearly up to 60 in April (above 50 signals net growth). This PMI series, which indicates direction rather than the level of activity, may be erratic for a while yet. But, with orders and backlogs seemingly improving, SW businesses are looking for a stronger end to the year. Costs remain a concern and, with capacity somewhat constrained, price rises have already occurred, and more are expected. Nevertheless, “survivors” from the pandemic seem to anticipate better trading conditions for the rest of 2021. Surely, the worst lockdowns are behind us.

In other words, there are reasons for optimism in the near term and opportunities for growth and investment further out. There are also reasons, however, for uncertainty about approaching and future outcomes, with high risks around any current forecasts or planning. The bottom line is to bolster firms’ financial and capacity defences for prolonged adjustment whilst watching for the business, market, skills and technological opportunities for growth that are bound to arise.

Reading back this anniversary issue, it is a bit “on the one hand, this and on the other hand, that”. Such is often the case with economic futures, but particularly now amidst great uncertainty over all aspects of demand and supply, market access and policy. The “winners” will see opportunity, invest wisely, build productivity and prosper. The “losers” will fade and close, eventually releasing resources for more profitable utilisation. The process of adjustment will probably be lengthy, causing casualties and raising heroes. Here’s hoping Dorset businesses and agencies are ready and up for the challenge.